This post is also available in:

French

French

Paris – FRANCE

For many years I have worked with the most impoverished homeless people of Paris.

Along with about 60 colleagues, representatives from the ‘Recueil Social’, a support group from the public transport network in Paris (RATP), I have seen and lived through some very serious and complicated situations.

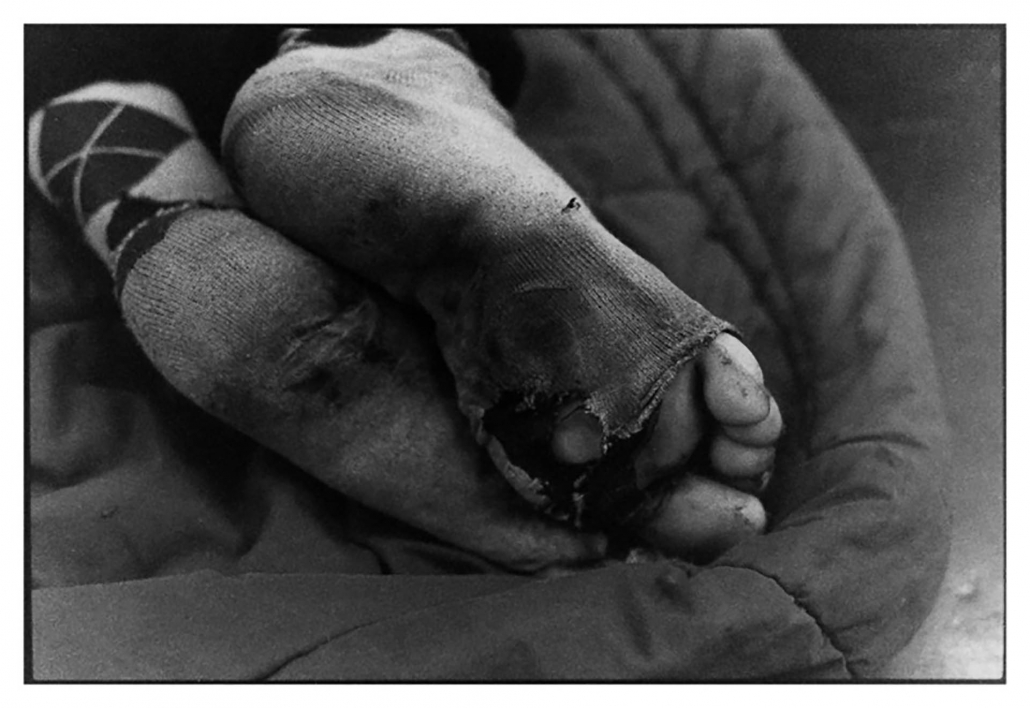

I have met hundreds of people for whom life is nothing more than tatters: lives broken by loss of work, failed relationships or illness; others complicated by a childhood scarred by violence, sexual abuse or abandonment. All these people have one thing in common, their ‘living’ place, the metro. The descent into hell accelerates in the metro. All grasp of reality is quickly lost down there. The day, the time, the weather… It all escapes these people.

With my colleagues, our work is to encourage these people to follow us and to get on board our bus that is provided uniquely for them. To do this we have little to offer other than coffee, cakes and soup. But above all they are able to find safety. With us, the homeless are safe.

We discretely make a quick assessment of the state of health and the needs of these people, people who we refer to as ‘clients’. It is with this quick assessment that, without imposing anything, we can direct the individual towards a place where they can find help: treatment, hygiene, meals, etc. And it is there where our work must stop. Each day however, our work takes on the same people to help, and always with the same problems.

Our task is difficult. The direct and everyday contact with extreme poverty, with these people who often confide in us, telling us the story of their life made of violence can often be itself a violent experience. We volunteer for this task, a task which is so different to our original careers (as station workers, security guards, train drivers, etc.). It is a very tough job but it is also very rewarding.

Bizarrely the most difficult aspect to cope with is not what we go through every day on our bus. No, it is the result of this work that is the most difficult aspect to cope with. This result is catastrophic. Alcohol and drugs have ultimately taken hold of our ‘clients’ and nothing can change their life.

Is this the reason why the support centres are so ineffective when it comes to taking in our ‘clients’? What is certain is that this failure of theirs is partly responsible for the failure of our own mission. A completely incontinent grandfather, a mentally unwell, a dropout; the support centres don’t want them. Does welcoming these people ask for too much work and time while their centres are already full of people with far more limited needs?

That is often how it appears to us.

Sometimes the people working in these support centres ask us, or rather make it clear that we should direct our socially maladjusted ‘clients’ to somewhere other than their centres, to the CHAPSA for example, a shelter that is generally seen as the last resort. We are sometimes left asking ourselves whether the CHAPSA is, for them, just a human dustbin…

For us however, the CHAPSA is the place where our most defenseless and impoverished ‘clients’ are given the best reception. The health assistants do a remarkable job in often deplorable conditions.

Over the course of these many years spent with the homeless of the Parisian metro, the observation that I take from my experience is simple and can be summarised as follows: ‘nothing, or almost nothing’.

It is most often with death that our ‘clients’ are freed from this ‘life’.

Nothing else.

LA GRAN EXCLUSIÓN

París – Francia

Durante muchos años he trabajado con los SDF (sin domicilio fijo) más pobres de París.

Junto a sesenta colegas, otros agentes sociales de la RATP (red del transporte subterráneo parisino), tuvimos la ocasión de ver y vivir situaciones graves y complicadas.

Encontré cientos de personas cuyas vidas habían volado en pedazos. Vidas destruidas por la pérdida de un empleo, un duelo, un divorcio, una enfermedad. Otras por una existencia aún más complicada con una infancia en familias violentas, abusivas, con padres violadores o por abandono. Todas estas personas en su mayoría con un denominador común: la vida en el subterráneo parisino (le métro).

Y es en ese subterráneo que el descenso al infierno se acelera. La pérdida de referencias es muy rápida. ¿Qué día? ¿Qué hora? ¿Qué tiempo? Muy pronto todo eso se desvanece y se esfuma.

Con mis colegas, nuestro trabajo era incitar a estos individuos a acompañarnos para acogerlos en un autobús puesto a su disposición. Sin mucho que ofrecerles: una taza de café, biscochos, sopa pero sobre todo seguridad. Con nosotros estos indigentes se sabían seguros.

Discretamente, hacíamos un diagnóstico rápido del estado de salud y de las necesidades de cada individuo que nos pedían llamar “clientes”. Con esta rápida evaluación los dirigíamos, sin imponer nada a nadie, a un lugar donde podrían encontrar ayuda, cuidado, higiene, comidas, etc. Hasta ahí llegaba nuestra misión. Sin embargo, todos los días, nuestro trabajo recomenzaba a menudo con la misma gente y con los mismos problemas.

Nuestro trabajo es difícil. El contacto directo y cotidiano con la extrema pobreza de aquellas personas que a veces nos confían su vida hecha de rupturas y agresiones, es también violento. Nos ofrecemos para este trabajo muy diferente de nuestro trabajo inicial (agente de estación, agente de seguridad, mecánico, etc.). Un trabajo muy duro, pero que aporta también sus recompensas.

Curiosamente, lo más difícil de soportar no es lo que vivimos todos los días en nuestro bus. Lo insoportable es el resultado de este trabajo. Un resultado catastrófico ya que el alcohol y las drogas encadenan a nuestros “clientes” y ya nada puede cambiar sus vidas.

Es por eso que los centros de alojamiento y desintoxicación fallan también en el cuidado y el tratamiento de nuestros “clientes”? Lo seguro es que esta falencia es en parte responsable del fracaso de nuestra misión. Un abuelo totalmente incontinente, un enfermo mental, un vagabundo marginal, los centros no quieren recibirlos. La recepción y el cuidado de estas personas implican demasiado trabajo, demasiado tiempo, cuando estos establecimientos ya están completos de gente con necesidades menos importantes.

Esto es a menudo lo que vemos.

A veces los agentes de estos centros encargados nos piden o nos hacen entender de depositar nuestros “clientes” más difíciles fuera de sus instalaciones, en un CHAPSA por ejemplo (Centro de recepción y alojamiento para sin domicilios fijos). En su forma de ver las cosas, el CHAPSA sería como un centro de tratamiento de basura, humana…? Nos lo preguntamos a veces.

Sin embargo, para nosotros es en un CHAPSA donde nuestros “clientes” los más degradados reciben la mejor atención. Los asistentes médicos hacen un trabajo meritorio en condiciones a menudo deplorables.

Durante estos largos años en contacto con los vagabundos del subterráneo parisino, mi conclusión es muy simple: “nada, o casi nada.”

Muy a menudo nuestros “clientes” son liberados de esta “vida” a través de la muerte.

Nada que agregar.

Lionel SAINT-LÉGER