Violence Against Women in Papua New Guinea

Vlad SOKHIN

This post is also available in:

Anglais

Anglais

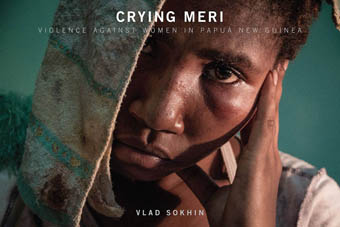

Immédiatement au nord de l’Australie, on trouve la Papouasie Nouvelle-Guinée (PNG). L’extrême pointe de cette île est située à moins de cinq kilomètres des côtes australiennes. Pourtant la vie des femmes dans cette nation insulaire est à des années-lumière de celles de leurs voisines australiennes.En Papouasie, près de 95 % des femmes, appelées “meri” dans le dialecte local, travaillent dans des fermes pour subvenir aux besoins de leurs familles. Leur vie est dure dans tous les sens du terme, et elles ont peu d’opportunités de se libérer de leur condition du fait des restrictions dues à la tradition, à la pauvreté, à la superstition et au manque d’éducation.Comme si ces fardeaux n’étaient pas suffisants, les femmes de Papouasie sont aussi sujettes à des violences domestiques et à des agressions sexuelles dans des proportions qui semblent inconcevables ; plus de deux tiers d’entre elles souffrent d’abus horribles de la part de leur mari, et beaucoup restent défigurées après avoir été attaquées avec des couteaux et des haches. Cinquante pour cent des femmes de Papouasie Nouvelle-Guinée ont été agressées sexuellement, mais ces chiffres augmentent exponentiellement dans les provinces les plus reculées, où dans certaines zones, 100% des femmes sondées ont été violées. Le viol est endémique et sert de rite de passage pour les gangs Raskol qui rôdent dans les rues de la capitale, Port Moresby.Pourtant les statistiques peuvent paraître dérisoires quand les chiffres cités sont si chargés d’émotions qu’ils deviennent incompréhensibles ; il est bien beau de parler de proportions endémiques ou d’affirmer, comme le fait l’Onu, que les femmes de Papouasie font face aux plus hauts niveaux de violence dans le monde. Mais qu’est-ce que signifient vraiment ces chiffres de 50, 90 ou 100 pour cent ?Ouvrez le nouveau livre du photographe documentaire Vlad Sokhin, Crying Meri: Violence Against Women in Papua New Guinea, et très rapidement, les statistiques deviendront des êtres humains, des femmes dont la vie a été brisée comme l’ont été leurs os. Leur corps est marqué à jamais et leurs yeux traduisent silencieusement la terreur provoquée par les nombreux coups et agressions, beaucoup infligés des mains mêmes des membres de leurs familles. Regarder ailleurs, c’est leur dénier une voix, que Sokhin a travaillé sans relâche à leur offrir.Sokhin, qui est d’origine russo-portugaise, dit qu’il a découvert cette réalité par hasard en 2011 quand il s’est installé en Australie. « Quand vous êtes free-lance, vous recherchez des sujets. Je lisais des choses à propos de la Papouasie Nouvelle-Guinée quand je suis tombé sur une étude sur la violence contre les femmes âgées d’une vingtaine d’années. Cette étude affirmait que dans certaines zones, presque 99 % des femmes étaient sujettes à des formes de violence, y compris des actes liés à des accusations de sorcellerie. J’ai trouvé cela très choquant. En tant que photographe, j’ai commencé à chercher les preuves en images de cette violence et je n’ai rien trouvé d’autre que des clichés isolés qui accompagnaient quelques articles. Il m’a alors semblé que personne n’était vraiment intéressé par la question ou n’avait eu l’opportunité de la traiter jusque-là, et je me suis dit, eh bien, pourquoi pas moi ? »Après avoir proposé le sujet à quelques publications, et n’avoir obtenu aucune réponse, Sokhin a décidé de prendre un risque et de se lancer seul.

CRYING MERI

Violence Against Women in Papua New Guinea

Vlad SOKHIN

FotoEvidence Editions

2014To Australia’s immediate north lies Papua New Guinea (PNG), its most southern tip less than five kilometres from Australia’s mainland. Yet life for women on this island nation is light years away from their Australian neighbours.In PNG around 95 per cent of women, known as “meri” in the local dialect, work on farms to provide for their families. Their lives are hard in every sense of the word, and there are few opportunities to break free when one is shackled by tradition, poverty, superstition and lack of education.If these burdens are not enough, the women of PNG are also beset by domestic violence and sexual assault at rates that are inconceivable; more than two thirds of women suffer horrific abuse at the hands of their men and many are left disfigured after being attacked with knives and axes. Fifty percent of women in PNG have been sexually assaulted, although this figure climbs alarmingly in the more remote provinces, where in some areas 100 percent of women surveyed have been violated. Rape is also endemic, a right of passage for the Raskol gangs that prowl the streets of the capital, Port Moresby.Yet statistics can mean very little when the numbers cited are so loaded with emotion they become incomprehensible; it is all well and good to talk about epidemic proportions, or to claim as the UN does that PNG women face among the highest levels of violence in the world. But what does that figure, that 50, or 90 or 100 per cent look like?Open the cover of documentary photographer Vlad Sokhin’s new book “Crying Meri: Violence Against Women in Papua New Guinea” and very quickly these statistics become human beings, women whose lives have been shattered along with their bones. Their bodies are indelibly scarred and their eyes silently scream of the terror of numerous beatings and assaults, many at the hands of family members. To look away, is to deny them a voice, one that Sokhin has worked tirelessly to give them.Sokhin, who is of Russian/Portuguese descent, says he happened upon this story by chance in 2011 when he moved to Australia. “When you freelance you look for stories. I was reading about PNG when I found a survey about violence against women that was about 20 years old. This survey claimed that in some areas almost 99 percent of women were subjected to brutal forms of violence including sorcery-related violence. I found it very shocking. As a photographer I started to look for photo evidence of the violence and I couldn’t find anything other than single pictures that accompanied a few articles. It seemed to me that no one was really interested or had a chance to cover it before, and I thought, well why not me?”After pitching the story to a few publications, and getting no response, Sokhin decided to take a gamble and go on his own.

CRYING MERI

Violence Against Women in Papua New Guinea

Vlad SOKHIN

FotoEvidence Editions

2014To Australia’s immediate north lies Papua New Guinea (PNG), its most southern tip less than five kilometres from Australia’s mainland. Yet life for women on this island nation is light years away from their Australian neighbours.In PNG around 95 per cent of women, known as “meri” in the local dialect, work on farms to provide for their families. Their lives are hard in every sense of the word, and there are few opportunities to break free when one is shackled by tradition, poverty, superstition and lack of education.If these burdens are not enough, the women of PNG are also beset by domestic violence and sexual assault at rates that are inconceivable; more than two thirds of women suffer horrific abuse at the hands of their men and many are left disfigured after being attacked with knives and axes. Fifty percent of women in PNG have been sexually assaulted, although this figure climbs alarmingly in the more remote provinces, where in some areas 100 percent of women surveyed have been violated. Rape is also endemic, a right of passage for the Raskol gangs that prowl the streets of the capital, Port Moresby.Yet statistics can mean very little when the numbers cited are so loaded with emotion they become incomprehensible; it is all well and good to talk about epidemic proportions, or to claim as the UN does that PNG women face among the highest levels of violence in the world. But what does that figure, that 50, or 90 or 100 per cent look like?Open the cover of documentary photographer Vlad Sokhin’s new book “Crying Meri: Violence Against Women in Papua New Guinea” and very quickly these statistics become human beings, women whose lives have been shattered along with their bones. Their bodies are indelibly scarred and their eyes silently scream of the terror of numerous beatings and assaults, many at the hands of family members. To look away, is to deny them a voice, one that Sokhin has worked tirelessly to give them.Sokhin, who is of Russian/Portuguese descent, says he happened upon this story by chance in 2011 when he moved to Australia. “When you freelance you look for stories. I was reading about PNG when I found a survey about violence against women that was about 20 years old. This survey claimed that in some areas almost 99 percent of women were subjected to brutal forms of violence including sorcery-related violence. I found it very shocking. As a photographer I started to look for photo evidence of the violence and I couldn’t find anything other than single pictures that accompanied a few articles. It seemed to me that no one was really interested or had a chance to cover it before, and I thought, well why not me?”After pitching the story to a few publications, and getting no response, Sokhin decided to take a gamble and go on his own.

NEWSLETTER

Pour recevoir nos informations, inscrivez votre adresse email.EN SAVOIR PLUS

Pour Que l’Esprit Vive,

Association loi 1901 reconnue d’utilité publique

Siège social

20 rue Lalande,

75014 Paris – France